I just caught up with Maria Schrader’s excellent new movie I’m Your Man (Ich bin dein Mensch), which came out in the UK last month.

Archaeological researcher Alma (Maren Eggert) is cajoled by her boss into serving as a participant in a scientific trial. Using interviews, studies, and brain-scans, a team of designers will create a lifelike robot intended to be her perfect companion. The result is Tom (Dan Stevens), an English-accented android programmed to meet her every emotional and physical need. Tom will live with Alma for three weeks, at the end of which she’ll write a report informing the decision on whether androids like him are allowed out into German society.

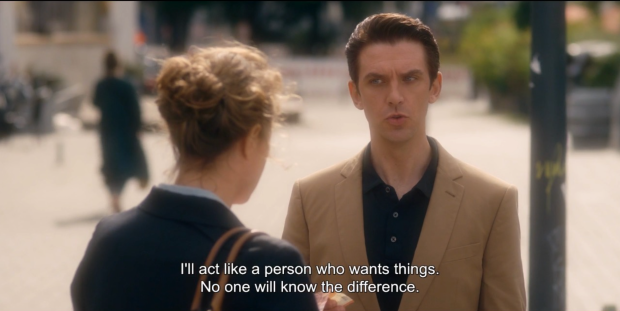

Things get off to a rocky start when Alma rejects Tom’s first schmaltzy attempt at wooing her, and a malfunction on the dancefloor mid-rumba doesn’t help matters. Once Tom has been fine-tuned by the manufacturer, he moves into Alma’s apartment and sets about tidying the place, preparing lavish breakfasts, and attempting to meet or anticipate her every whim, only to find his new mistress contrary, frustrating, and generally unwilling to pretend he is anything other than a machine.

Inevitably, there’s a thaw between the two, and for a while the film feels a little plodding; you wish that it had been shot in 1938, with Cary Grant as the android, so it had a bit more screwball zip. But something darker lies beneath the surface of Schrader’s movie, never quite coming to light, and by the end of the film you’re glad that this story is told exactly the way it is.

Alma’s father, suffering with dementia, requires regular care from his two daughters. On one of the visits, Alma and her sister rifle the family photo album and realise that Tom is modelled on a boy they both fancied when they met him on holiday in Denmark. As I’m Your Man hits various rom-com beats, and Tom proves as handy in supporting Alma’s research as he is in sprucing up her home, murmured questions of memory and desire arise.

Is it possible to truly have an authentic relationship with a machine whose purpose is romantic fulfilment? Is Tom really “there” – he certainly seems to have agency, and a wry sense of humour – or is his personality just ripples in a pond, compiled from data, emanating from a stone dropped long ago: a moment of real human contact and unfulfilled desire? Alma’s relationship with Tom is contrasted with her lingering connection to her ex, Julian, whose new life with a new partner threatens to undermine the remembrance of what he and Alma once had. The film reminded me of Adrienne Shelley’s Waitress, which similarly skirted rom-com territory and used a few home truths about what really attracts us to other people to puncture Keri Russell’s budding romance with Nathan Fillion.

In the exhortations of Tom’s manufacturer to build shared memories that will cement the cybernetic relationship, in Alma’s fear that Julian’s new life means the old one will be forgotten, in the way that the image of that Danish boy becomes a touchstone for Tom, Alma, and her sister, the movie also put me in mind of Hirokazu Kore-eda’s After Life, in which dead souls must choose one memory which they will inhabit for eternity.

It’s not by chance that Alma’s work involves deciphering ancient clay tablets, or that as an academic researcher she is in competition with rival scholars around the world, all hoping to be the first to crack an ancient mystery. How much of what we want is a second taste of something we remember, or a chance to re-play a long-gone yearning, Schrader’s movie seems to ask? How much are we looking for something new and spontaneous, and how is our “individual” desire shaped by the web of relationships around us? Alma struggles to let herself love and be loved, because of the particular ways she is entangled with the past. (Tom speaks German fluently, but explains that he has been programmed with a British accent because Alma is attracted to men who are neither completely familiar or entirely exotic: a halfway house of otherness and novelty).

The performances are excellent and the storytelling deft, with a number of smart feints and a carefully handled tone which means you’re never quite sure whether the film is going to veer entirely out of comic territory into something more disturbing. Schrader eschews melodrama and her film remains largely within the mundane space where many of us live our lives, noodling our way through the day-to-day with a few frustrations, a few successes, and a vague sense of not really knowing what we’re doing with our time on this earth.

I’m Your Man raises the question of whether the “comfort machines” of our smart age, each tailored by algorithm to one’s own requirements, will make us incapable of dealing with other people’s messy and difficult ways, and ultimately lead to the downfall of the human race. (We briefly see another test subject, who considers himself unlovable and whose android is a blank, bland, adoring doll in comparison to quirky, curious Tom). My mind made a strange jump to Charles Stross’ The Labyrinth Index, which is a supernatural thriller but says something about the possibility of a new world order where artificial intelligence dominates: in that novel, a character facing humanity’s inevitable extinction says, “We fight on so that something that remembers being human might survive.”

When the credits rolled, I talked about the film with a friend who is a lecturer in psychoanalysis, and he said the central question of artificial intelligence is whether robots will be able to desire. (Just the question you’d expect from a Freudian). I’m Your Man never fully comes out on one side or the other about what exactly is going on inside Tom’s head, or whether it’s even possible to know the difference between his simulated desire and an “authentic” one. Still, by the film’s end, you think: if such machines are going to outlast us, even if they’re only the ripples of the stones we’ve dropped in life’s pond, at least they’ll appreciate something of what it means to be human. They’re the cuneiform tablets of the swipe-right age.