“If thinking differently was going to make me a better runner, I could do it sitting in the pub.”

Charlie Spedding missed a train, bought a beer, and changed his life.

The English marathon runner, a pharmacist by trade, found himself in a pub forty years ago, pondering how to make the big time.

“I had committed myself to running when I walked away from my father’s business, but I didn’t seem to know how I was going to fulfil whatever potential I had. All I had done was burn my bridges, and I felt unsure about how to make progress.”

All lives come to turning points, by choice or by chance or by decisions over which we have no control. So how do we make the most of them? What options are available to us?

And can we drink our way to better librarianship?

In 1980, the 28-year-old Spedding was sitting in a Newcastle pub, facing an hour’s wait after missing the train home. He bought a pint of real ale and took out a notepad which he had bought that day in a bookshop.

He started with a list of things that he wanted to achieve – “improve my times”, “win more races” – but, as Spedding himself puts it: “I soon realised I had been trying to do those things for the past ten years.”

What was holding him back from greater achievement? What’s holding you back?

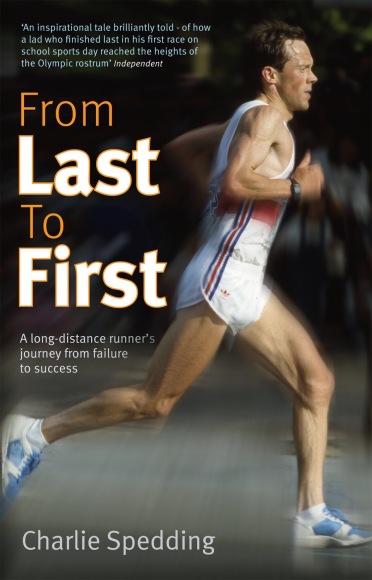

This is the first of a two-part discussion about drinking your way to better librarianship. Today we’ll look at Charlie Spedding’s experience, as recounted in his book From Last to First. Next time, we’ll be joined by a special guest whose job involves training library workers and preparing them for a bright future.

You don’t need a pint of beer for these exercises, but you’re welcome to one if you fancy. A cup of tea would work just as well – or whatever you prefer to sip as you meditate.

You will need a notepad and pen, though.

1. WHAT DOES SUCCESS LOOK LIKE?

“For years,” Spedding writes, “I had assumed that my failure to run better was down to a combination of injuries and not training hard enough, but I started to wonder if it was my own self-image that was holding me back.”

After all, Spedding had once been the boy who was bottom of his class, clumsy at soccer, who had to retake his school leaving exams to enter higher education and become a pharmacist.

“I had never done anything to suggest I was going to be better than average,” he writes, and then: “I consoled myself with a mouthful of beer, and kept the delicious flavour in my mouth while I wondered what to do.”

“Eventually I decided to swallow it and I began to smile. Whenever I have a problem, I always feel better about it when I know what’s happening. […] I wasn’t worrying too much about how I was going to change 28 years of uninspiring, accumulated experience. I was simply happy that I was going to try to do it.”

Spedding, drinking the beer, began to question his own perspective on sport.

“To most people my attitude would have seemed good; I trained twice a day come rain or shine; I had come back many times from serious injuries, and I had even given up the opportunity of my father’s business to pursue my sport. But I was starting to realise that although I had an attitude that made me diligent in my training, it wasn’t the same thing as having an attitude that would make me successful in my running.”

Training hard would never be enough. “Even If I had done some excellent training, I could always tell myself I could have done more, or I could have run quicker.”

Spedding wanted to be successful, which meant being better than average. “I had to be different to most people if I was going to be better,” he writes. “I needed to do, say, and think things in a better and different way.”

Spedding found it hard to define success. He felt unsure what he was capable of achieving – for all his victories, medals, and championships, the future was an unknown and any goal he set might be too ambitious, or not ambitious enough.

Perhaps, he thought, he could focus on his individual potential. If success is measured by how you fulfil the talent you were born with, this is a definition which anyone could use. It wasn’t about comparing yourself with other people, only comparing yourself against your past.

“It hit me. If I kept it going until I truly fulfilled whatever talent I had, I couldn’t be more successful. Nobody could be more successful. I may not win the prizes and acclaim of someone with more talent, but I could be just as successful as them.”

Spedding picked up his pen and made a note on the pad beside his pint. Under the heading “What do I want?” he wrote: “I want to feel fantastic. I want to feel absolutely fantastic.”

“I liked the idea that I had to be different to most people, if I was going to become better than average. I really liked the idea that it didn’t mean I had to train harder than everybody else, because it was dawning on me that I needed to think differently to everybody else, and by thinking differently, I could develop an attitude of success.”

“This sounded great; if thinking differently was going to make me a better runner, I could do it sitting in the pub. I smiled to myself and took another drink as I figured I was making myself a better runner right now.”

What does this mean for a knowledge worker like a librarian?

Take a sip

- What does success look like for you?

- What does success look like for your institution?

- What does success look like for your profession?

- Write down your answers. Where do those three perspectives overlap, coincide, or clash? Where are the points of tension, where are the opportunities?

2. JUST A PERFECT DAY

“Having crazy concepts was fine, as long as I could turn them into something practical.“

For Spedding, the psychological change was in his vocabulary.

“When I missed all the steps out and wrote down ‘improve my vocabulary = run faster’ I thought it sounded crazy. But then I remembered that I had already decided to think differently to most people, so I wrote ‘think differently’ as a heading above it, and suddenly it became a legitimate idea.”

Spedding had already decided it wasn’t about training hard. Although the work had to be done to provide the chance of success, he only needed to train to his optimum level – enough but not more.

He imagined running track sessions. Sometimes you went hard in the final laps, trying to prove yourself you could do more or go faster. On those days you trained hard – but psychologically, was it valuable? It had the potential to leave you questioning whether your original goal was good enough, whether you should have run faster all along.

Spedding instead imagined running consistently to the required pace. “I would have achieved exactly what I set out to do, and could feel satisfied with a job well done…Everytime I achieved what I set out to do, I was going to call it perfect.”

If Spedding was left behind by his partner on last two laps, no drama: “My training was perfect, but his was hard.”

Spedding’s plan was to accustom himself to perfection. On race day, it would no longer be a case of “running harder than ever”, it would be about running the perfect race – something he did all the time in training.

Take a sip

- What would “perfection” look like in your role? Not overwork, or heroic measures, or “going above and beyond” – but simple, pure, and sufficient perfection?

3. WANTS AND NEEDS

“I was sure that it was almost impossible to achieve a performance that my mind, or self image, thought was beyond me. So perhaps I had to imagine myself as a better runner before I could become one.”

Spedding says his pub-born approach was never about the world-beating championship fantasies to which we are all prone.

Spedding was always a realist about positive thinking:

“No matter how positive my thinking was, I would never be a sprinter or high jumper, because I didn’t have the fast-twitch muscle fibres to do it. I decided that you can’t do anything with positive thinking, but you can probably do everything better than you would with negative thinking.”

Instead, he sought a precise language and way of thinking to make him more successful. His interest was in using imagination and mental rehearsal to achieve better results. “I would train my mind to accept the reality of the performances I imagined.”

For a runner, participating in a competitive and measured sport, it would require some clearly defined steps. Spedding knew his long term goal was fulfil all the potential of his talent, but would that look like over life’s many stages?

What did he want? Why did he want it? And how much did he want it?

The latter question was key. “That crunch moment in a race would be altered by why I was doing it, but it could be transformed by how much I wanted it.”

Take a sip

- What do you want from your career?

- Why do you want it?

- How much do you want it?

- What will you sacrifice or commit to pursue your goals?

4. THE VERY HUNGRY CATERPILLAR

Spedding recognised that doing things differently would sometimes make him stand out. Even in the pub, he got teased for sitting alone scribbling while others were socialising.

Someone from another table called him Einstein; he thought to himself, Einstein was a very smart guy, but I’m pretty sure I could have thrashed him over 10K.

Spedding was coming to another realisation: “The way to deal with this was to embrace it, have fun with it, and try to enjoy it.”

He tried to find some imaginary source of inspiration and identification. What would guide him on his offbeat path to better running?

He tried to imagine himself as a famous runner from the past, but that didn’t fit his definition of success as fulfilling his own unique personal potential.

He thought about the animal kingdom. Cheetahs were the fastest runner on the earth, lions were kings of the jungle; eagles soared high. But Spedding’s self image wasn’t built on innate special qualities.

Instead, his mind took him to the bottom of his own garden.

On his pad, next to the pint, he wrote, “I am going to think like a caterpillar.”

As Spedding puts it,

“The caterpillar spends its time surviving. It hides from birds and eats leaves, but it is one of the most ambitious creatures on the planet because all the time it is thinking, ‘one day I am going to grow beautiful wings and I am going to fly.'”

Spedding decided to be a caterpillar, a creature which needed time and the right conditions to fulfil all its incredible potential.

Take a sip

- If you were an animal, what animal would you be?

- What makes your job fun?

- What can you laugh at about yourself, your life, the ups and downs of your career to date and your career yet to come?

5. OLYMPIANS

Spedding concluded his ponderings by writing a summary of all he had learned in an hour spent alone with a pint of beer:

“Change my vocabulary. Aim for perfection. Know what I want, why I want it, and how much I want it. Use my imagination. Try to feel fantastic, and think like a caterpillar.”

Spedding was excited. He knew that there would be a further challenge ahead – recognising and accepting the day when the caterpillar must make its final effort and transform, take flight – but in the meantime he could get to work.

He finished his pint, went for the train – and four years later, he’d win the Houston Marathon and the London Marathon, plus an Olympic bronze in Los Angeles.

Not all of us will become Olympians in our chosen endeavour, but if you commit to fulfilling your own personal potential, a day like Spedding’s is waiting for you, too.

“It is very difficult to cross the boundaries of the map we all have tucked away in our heads, because our subconscious minds always want to guide us to somewhere familiar and safe. Our accumulated experience tells us who and what we are, and our minds make us act in a way that fits our own particular comfort zone.”

So, whether you have a cup of tea or a pint of beer or something else entirely, take a sip and have a think: can you drink your way to better librarianship?

Join us next time for more on where the profession might be headed – and how to drink your way to better librarianship.

One thought on “Drink Your Way To Better Librarianship”