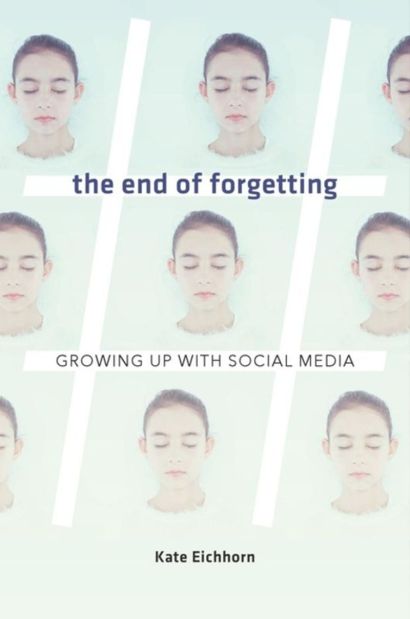

I’m proud to present a Q&A transcript with the New School for Social Research’s Professor Kate Eichhorn, author of The End of Forgettting.

We spoke earlier this year to discuss who gets to tell their own story in the age of social media, what are the consequences to such stories being shared, and what power do we have to forget or be forgotten in this new digital era? This conversation formed the basis for an instalment of “Scripturient”, my column in Information Professional magazine, but now you can read a Q&A expanding on that text, below.

Matt: When did the idea for The End of Forgetting coalesce?

Kate: Prior to working on this book, I had been thinking about and writing about archives for many years. There was a moment when I literally asked myself, what’s after archives? I immediately thought, it’s forgetting. But all of my colleagues who work in archives were very quick to remind me that the archive and forgetting are inextricably linked. So, this book was a kind of natural extension of my earlier work on archives. But the book, while not a personal book, is informed by personal circumstances. On the one hand, when I started working on the book, my kids were maybe 11 and 13, so I was certainly thinking about the tween girls and their relationship to social media. As a parent, I also started to think about how different my life would have been had I been on social media when I was their age. I am almost certain that I would have either said or done things I would have regretted and that there would have been consequences.

Matt: In terms of your journey towards a concern with the archive, was there something that pulled you initially to this sector – an interest in memory and forgetting?

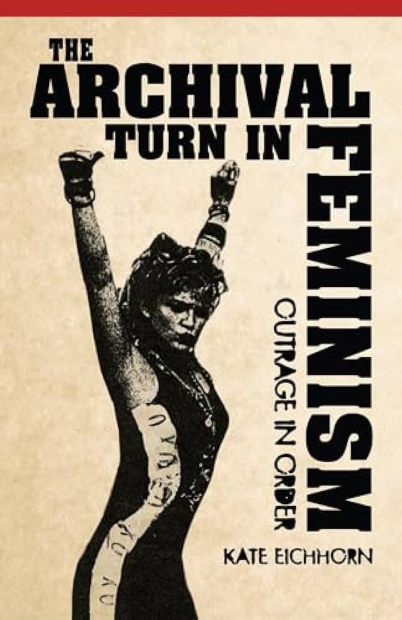

Kate: That’s an interesting question. I think that back in ‘94 or ‘95 when I started graduate education, everything was shifting very quickly for those of us attempting to investigate emerging virtual spaces. At some point around ‘99, when I was about to start writing my dissertation, which was originally going to focus on hate speech and cyberspace—and we now know that turned out to be a problem that just kept growing—I felt things were moving so quickly, I needed to turn my focus back to an earlier media transition. For a while, I ended up in the world of book history. In the end, my dissertation was a comparison between the first few decades of print culture and emerging digital cultures and some of the parallels between these periods. That’s when I started to get excited about doing archival research and thinking about the archive as a space and not just a space where you got to access dusty old documents but also as an ethnographic site. Later, in my first book, The Archival Turn in Feminism, I begin to theorize archives as a site of knowledge production and explore the relationship between the past and present, particularly in relation to activism.

Matt: Going back to the history of the book and the comparisons you made in your dissertation, there’s this sense where different eras sometimes seem to rhyme. Do you have a sense of what can be done with that, or how that nourishes actions or perspectives that we might take now? What are the benefits of seeing these parallels even centuries apart?

Kate: There’s an incredible benefit to this type of comparative thinking if you don’t over-determine the parallels. For some time, everyone was talking about the “internet revolution” and now everyone’s talking about the “AI revolution.” We like to overdetermine the moment we’re living in. A long perspective reminds us that we might not be experiencing something as new as we assume. The book I’m working on now is about the history of school yearbooks, but the subtitle is “The Long History of Social Media.” I make the case that yearbooks were essentially a print-based example of a social media platform and explore some of the ways in which these books, which may seem innocuous, in fact, share many of the problems we are now grappling with on social media platforms.

Matt: I worked on my high school yearbook, and it was the most agency we ever had to be funny and creative in an institutional publication. It was probably the most liberty we had to be ourselves as we put in-jokes in our biographies and edited this community self-portrait, bio by bio. It made me think: even Facebook began within a college environment.

Kate: Well, in fact, before Facebook, the first social networking site was Classmates.com. It preceded Facebook by several years. It’s worth noting that the company that owned Classmates.com, eventually bought up a bunch of yearbooks and started to digitize them as a way to attract people to the platform, especially after Facebook came along and started cutting into their user base. What is interesting about that history is that Classmates.com failed because it charged people $35 a month to join, while Facebook and other social media sites were free, so, of course, most people chose Facebook.

Matt: Maybe that $35 a month is the alternative. Do you give away your privacy for a “free” service or stump up the cash?

Kate: Clearly, most people were more willing to give away their privacy, though they were also giving away their privacy on Classmates.com as well. Of course, this was the early 2000s–a time when we were also going online, tagging all our photographs with very valuable metadata—and doing so with no idea at all that we were helping create data sets that would later be used to essentially build facial recognition technologies.

Matt: Do you have a sense that there’s a way out of the Gordian knot we’ve tied ourselves in with regards to privacy and forgetting? Or is it, as the book’s title suggests, the end of forgetting — forgetting is simply done?

Kate: First, I have to say that it’s a very provocative title. I think it’s a good title and it worked, but it is also very provocative. It maybe would be better to say that what we’re dealing with is the diminishment of forgetting. But in terms of getting out of the situation we’re in, there are things that you can do to mitigate the damage—certainly in Europe, and particularly in the UK, there is legislation to help manage digital privacy and children’s privacy rights. But I don’t think we can entirely get out of the situation we’re in. I’ll add here that in the United States, things change because there’s a monetary motivation. But can we ever find a way to make as much money through forgetting as we did through remembering? Likely not, which makes it difficult to imagine a solution in this context.

Matt: We talked about the rhymes between the early days of the book and the internet age. In terms of your work in the zine archive, for example, do you also see these issues of forgetting as well as remembrance? In some ways, it’s much more an activist community trying to write a story and put something within a space where it will be preserved. But are there similar dynamics of memory and forgetting that had already arisen?

Kate: If you look at the feminist zines from the early 1990s, many of which have ended up in archives across North America, many of them were comprised of recycled texts and images taken from Second Wave feminist magazines and books. So, as opposed to representing this kind of radical break with the past, which is how feminist zines from that era were originally seen, I have always insisted that these zines seem to express an incredible longing for the past In fact, there was an intentionality about the need to preserve the past and zines, and later the archiving of zines, were part of this labor. But the 1990s was also a time when we saw the collapse of most feminist presses and bookstores, not only in the United States but also in countries where these endeavors were more likely to have had some state support. So, there is also a relationship between the rise in neoliberalism and this turn to history and archives.

Matt: Are there, or were there, any hopeful spaces that managed to endure into this later phase of the Internet – ones that echoed what zine culture once had offered?

Kate: Tumblr was a really optimistic space. I think a lot of people would agree that it was, at least until it become heavily censored, an online space that had some of the energy ethos of zines. At one time, it was also a very queer- and trans-positive space.

Matt: In the same way that you saw there was a continuity of feminist thought into zines, can you see movements or currents or positions that have been successfully carried over into online spaces – something of hope and endurance?

Kate: I think we’re not alone in looking for these spaces, but do they exist or can they exist? An interesting example is a site called Autostraddle, which is a feminist space that operated as a social media platform for many years and entirely outside of the corporate realm. In fact, users paid a subscription fee, which is part of the reason they were able to rely very little on advertising and to heavily vet the advertising that did appear. Just recently, the site changed hands, and although the new owner is a trans BIPOC entrepreneur, they are also a partner in a venture capital firm, so it seems like this one rare example of a social media platform that had found a way to exist on the margins of this dominate model may also be over. I think the problem is that alternatives to the dominant model simply aren’t scalable so, even if they are successful, their success can, ironically, also lead to their demise. I suppose scale requires embracing the very things that a lot of activists are opposed to.

Matt: So, there’s no escape.

Kate: Probably, not, because that would require being entirely off the grid, which is not possible.

Matt: You talked about this fantasy of being off the grid—I think you even use the word abstinence at some point in The End of Forgetting.

Kate: Yes, digital abstinence.

Matt: I suppose the flip side is the idea of hiding things or, or achieving some version of privacy through saturation. In Malka Older’s science fiction novels, there’s a character who deliberately enrolls in a PhD so that everyone in this information-rich environment will see they’re not lying about the fact, despite the fact it’s actually a cover. I wonder if there is a possibility to forget through sheer saturation, or privacy through layers of cover?

Kate: When my book on forgetting was published, millennial reviewers of the book were quite negative. Many concluded that no one really cares anymore because there’s so much information and, well, no one’s really looking. Another critique of the book is that what we see online is highly curated, so it’s not necessarily just a series of regrettable moments captured and preserved for life. In a way, both of these things are true. There’s a lot of information out there even about us personally. I also don’t think that people are going online trying to dig up dirt on me most of the time, but if I’m applying for a job, I know search firms—or the third parties they hire—are definitely digging up a ton of information on me. They are not just going to my LinkedIn or faculty page. They’re looking at other things, even my credit history. So, I don’t totally buy the privacy through saturation argument, because when people want to find information, there is a lot more information out there now to be found. Of course, it has different consequences for different people. In 2018, we were all analyzing the lewd remarks in Brett Kavanaugh’s high school yearbook, but that didn’t seem to matter in the end.

Matt: Talk about the bizarre power of forgetting: Kavanaugh feels like so many cycles back in American domestic politics.

Kate: So true, who remembers life in 2018?

Matt: In the situation we find ourselves in now, are there opportunities to use the digital tools and platforms in ways that weren’t intended?

Kate: Back to the optimism question! When I’m teaching, I always like to remind my students that the early history of the internet was an incredibly liberatory moment. People were logging on to GeoCities and going into MUDs and MOOs and reinventing themselves. Many people were multi-gendered. Maybe they were part animal or had horns or wings. This was all a possibility because you didn’t have to verify your identity back then. You could just create a Hotmail account with a crazy handle and start exploring. You never had to upload a scan of your driver’s license or verify who you were. As the internet became more monetized, and that happened by the early 2000s, we were being asked to verify our identity on an increasing basis. In the process, the Internet became a space of reality and not fantasy.

But to answer your question, I feel like there are moments when new platforms are introduced when we still see a bit of this experimentation. Perhaps it’s happening right now with AI, but then everything gets clamped down very quickly. So, I do think we have moments, fleeting moments at the beginning of a new app or platform, and then it’s gone. Partly because I think not having constraints at first helps attract users and generate content, which is advantageous for developers, but once the platform is up and running, you can impose censorship without comprising the revenue-generating potential of these platforms.

Matt: It all makes me think of Jose Esteban Muñoz and the idea that queerness will always escape taxonomies, that it will always be the thing that refuses to be pigeonholed, and how that sits with the desire to categorize and monetize social activity online. As you described with the MUDs and the MOOCs, there are these moments of mutability that feel liberatory.

Kate: True, I think queer people have a long history of occupying those spaces and helping define them and then are often erased from those histories as well.

Matt: Questions of pace and scale have come up throughout this discussion as well as throughout your book. It feels as if things are moving so fast, and that when you scale up, you can’t have these small communities in the same way. Reflecting on your practice, I don’t know if you’d characterize yourself as a historian or some other kind of scholar, but I wonder if there’s a way you use the past and the archive and a sense of context to swim upstream against the dominant or de facto notions of the pace we should be living at, or the scale we should be networking at.

Kate: I definitely would not refer to myself as a historian because I know that no historian would ever categorize my work as history. I really think about myself as a cultural studies and media studies scholar. And, so, I’m just trying to grapple with scale. As I said at the beginning of the interview, the reason why I suddenly went from researching the internet to book history was, quite literally, because I wanted to slow down and look at media transitions moving at a slower pace and, perhaps, on a more manageable scale, too.

Matt: We need improper historians as much as proper historians, perhaps.

Kate: Thank you for saying that!

Matt: What might you like to explore or research next?

Kate: I’m beginning to work on a collection of essays about the demise of feminism and gender equality, particularly in the United States, over the last decade or so. This book is still taking shape, but it feels like a politically important book to write at this time. Let’s just say, it won’t be particularly uplifting but, then, most of my books aren’t.