Occasionally, I write a post in the spirit of “showing your working”: playing with one or more concepts, seeing how they fit together, what use can be made of them.

In today’s long read, I’m looking at the work of Alfred Gell, an anthropologist whose book Art and Agency explored the social efficacy of art: the way that artworks and the process of making them influences the thoughts and deeds of others.

If we take scenarios and other strategic artefacts as art-objects, what can Gell tell us about their making, their use, and impact?

Vessels for thought: the last works of Alfred Gell and Richard Normann

Is there a distinctive way that people write when they know that the end is close?

The poet, literary scholar, and scenario planner Betty Sue Flowers has called death “the bald scenario“, with visions of the afterlife offering us the ultimate hindsight. “We can never stop thinking about death,” she writes, “as if from the other side — as if we were survivors — even though we don’t believe in an afterlife.”

In a subsequent book, Presence, Flowers and her co-writers reflect on “the requiem scenario”, inspired by a colleague who received a terminal diagnosis.

“Something amazing happened,” the man relates. “I simply stopped doing everything that wasn’t essential, that didn’t matter. I started working on projects with kids that I’d always wanted to do. I stopped arguing with my mother. When someone cut me off in traffic or something happened that would have upset me in the past, I didn’t get upset. I just didn’t have the time to waste on any of that.”

Later, the man was rediagnosed by a new doctor, who found that he actually had a rare form of a curable disease.

“When I heard this over the telephone,” the man said, “I cried like a baby – because I was afraid my life would go back to the way it used to be.”

I recently read works by two writers who knew their remaining time was short. The late Richard Normann, a storied management consultant whose legacy is commemorated in an annual lecture at Oxford’s Green Templeton College, died in 2003 after a long illness. In his latter years, he completed Reframing Business: When the map changes the landscape and the co-written People as care catalysts: from being patient to becoming healthy.

In humility, Normann’s foreword to Reframing Business reads:

I came to realise that it had simply become too comfortable for me to have others do much of the work. The time had come to do it all on my own. This probably has caused the book to be weaker than it might have been in some areas, but at least it has forced me to have a real workout session.

However, it’s also true to say that Normann was driven by a desire to get his thoughts out onto the page while he still could: to make sure that what he thought would live on in some form.

The same is true for the anthropologist Alfred Gell, whose final work Art and Agency was published posthumously in 1998. Gell’s wife Simeran describes how he “began the final chapter directly upon receiving confirmation of an uncurable condition”, working in an intense and almost trance-like state over three weeks of an Easter vacation.

Gell died just three days after sending the manuscript to his publisher; “he was pleased and grateful for being granted time enough in which to squeeze completion of a book on art … and was satisfied with the final product.”

Art and Agency offers an ambitious and provocative account of art as a form of instrumental action. It explores how we make art objects, from paintings and sculptures to abstract patterns and interior decor, in order to influence others — and how these objects are embedded in social relations. In doing so, it also gives us deeper insight into the manufacture and use of scenarios: plausible and contrasting depictions of the future context which can be used to inform strategic conversations and decisions.

It’s no wild claim to say that scenarios are aesthetic objects, which we respond to in the same way as we do to any artwork: how does this depiction of a plausible future make us feel?

You can compare scenarios to paintings or to Gothic literature; for Rafael Ramírez and Esther Eidinow, they’re an example of storytelling as a “technology of plausibility“. Ramírez and Angela Wilkinson also compare them to novels and to movies; as Ramírez and Jerome Ravetz put it, our aesthetic sense complements our capacity for rationality: “What one feels about something, what one senses … is the beginning of what one knows.”

The question of aesthetics plays a bigger part in consequential decisions than we might care to admit: do you choose the home you move into or the partner you settle down with based on a spreadsheet, or how they make you feel? When a jury decides a court case “on the balance of probability“, are they really running the numbers or are they persuaded by the side with the more compelling argument?

Given that Gell’s interest is in how artworks exert influence on our thoughts and actions socially, it’s no surprise that his theories are resonant with such an approach to scenarios, which are constructed for specific strategic purposes.

Taking this approach, new questions then arise: how do these strategic art-objects get made? Where does their meaning come from? How are they put to effective use? And what difference do scenarios actually make?

Art and Agency: An Overview

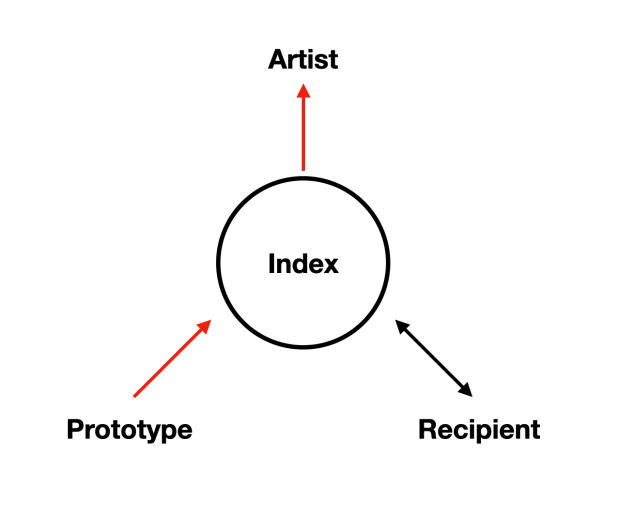

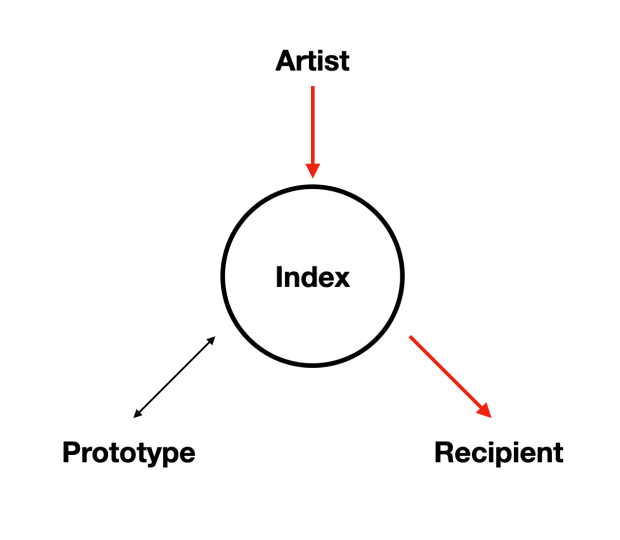

Gell refers to the artwork as an “index“. It mediates relations between the artist (the person who is considered to be the work’s immediate author), the prototype (the object or person which the artwork stands for or represents), and the recipient (those who are intended to be affected by the artwork).

Portraiture gives us a nice simple example: the artist makes the portrait; the prototype is the person whom the portrait is meant to represent; the recipient is the intended audience for the portrait.

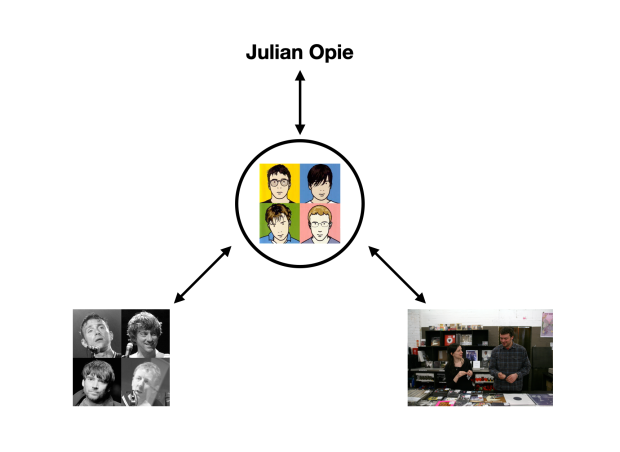

Take the stylised, cartoonish images of the band Blur on their Best Of album:

This “index” was made by the artist Julian Opie. Its prototype consisted of the members of the band Blur. The recipients were people who might purchase and play the record.

In Gell’s framework, each role can act on the other via the index.

The prototype acts on the artist when it dictates the appearance of the artwork. For example, when Julian Opie painted the members of Blur, merely by possessing certain facial features, they were dictating the nature of the artwork – it had to represent those features in some way that was recognisable. In photography, it’s even more evident how light emanating from the prototype, skillfully captured by the artist, affects the finished photograph or index.

Similarly, the artist can act on the recipient via their skill, wit, or powers, made evident in the artwork.

When we look at Nick Stathopoulos’ painting of Deng Adut, we marvel also at the skill of the artist in depicting the prototype or subject of the portrait. Even though the portrait feels almost photorealistic, we ponder who made this and how did they achieve these effects? The artist acts on us through the index even when invisible.

Each role can serve as either an “agent”, acting on another, or a “patient”, being acted on. Artists, for example, shape the prototype through their agency and intention in representing it. Tolkien’s choices in depicting the dragon Smaug help us to see what dragons look like generally – especially as we can’t find them in the real world.

Recipients can act on artists through patronage, by commissioning art and specifying what they want. (When the British monarch appears on the side of a 50p coin, the portrait has been created to meet the parameters specified by the Royal Mint).

Furthermore, the index itself can act directly on the other three roles, as well as being acted on by them.

The material of the index dictates the form which the artist creates, for example – you can achieve certain effects with charcoal, others with watercolours, others with CGI, and so on. In creative practices such as Japanese garden design or Marcel Duchamp’s readymades, an artist may simply “recognise” the potential of an object (whether an uncarved stone for the garden or Duchamp’s urinal) and place it in a setting just so, the index acting on the artist in this way.

In some societies, an index will be believed to act on a prototype through sorcery: damaging the representation of the victim will injure the victim themselves. And an index, of course, acts on recipients when we allow ourselves to become its spectator, irrespective of the artist or prototype.

It gets even more exciting – and intricate! – when we realise that, in Gell’s understanding, these roles can also act on themselves.

The artist, for example, acts on themselves via the index when they attempt to draw something they have never drawn before. They will visualise the prototype – Julian Opie picturing members of the band Blur. They will sketch out the lines they wish to make on the page, apply paint to canvas, use a mouse to move a cursor across a computer screen: but the line which appears will always be something of a surprise. The artist is a spectator as well as a creator of their own work: does that line look right? Erase it, do it again. Maybe if it curves a little more to the left. This is the work of “thinking through drawing” – where the hand, eye, and mind all work on one another through the drawing process – which Andrea Kantrowitz describes so eloquently in her book Drawing Thought.

Similarly, Gell’s recipients may commission an artwork as patrons, expressing agency – but then find themselves responding to the work, whether as a process or product: they find themselves impressed, disgusted, delighted, fascinated by the thing whose creation they themselves have ordered. And prototypes also act on themselves much as we do when we regard ourselves in the mirror, evaluating our appearance.

Gell offers the example of Graham Sutherland’s portrait of Winston Churchill. This is widely regarded as a penetrating study of its prototype, and very true to life – yet Churchill detested the portrait and, while acknowledging that it was “masterly in execution“, chose not to exhibit it publicly. (For a long time it was believed destroyed). Churchill, in his vanity, was the victim of his own actual appearance – the prototype of Sutherland’s artwork acting on itself.

Different relationships can also be nested within one another – like my diagram setting out the Julian Opie Blur artwork above. I have used a photograph of the members of Blur to stand in for the members themselves as prototypes, and another photograph of people in a record shop to stand in for the recipients of Opie’s work. But each of those photographs is itself an index, with its own set of relations to parse.

Gell gives another, elaborate, example of this: the “slashed” Rokeby Venus, a Velázquez nude which was attacked by the suffragette Mary Richardson with a kitchen knife in 1914.

Velázquez was the artist of an index, the painting representing the prototype of the Goddess Venus.

Richardson was protesting the treatment of Emmeline Pankhurt by prison warders. Gell reads this protest as an artistic act: Richardson, as an artist, takes Emmeline Pankhurst as her prototype. By doing violence to Velázquez’s canvas, Richardson creates a new index, the “Slashed” Rokeby Venus, in which recipients saw that Emmeline Pankhurst stood for modern womanhood much as the Goddess Venus stood for mythological womanhood. The “sufferings” of the painting served to evoke the sufferings of Emmeline Pankhurst in prison, and the scandal which ensued was an example of the power of art to influence social relations. (When the painting was restored, it also served to “wall up” the troubling feelings which Richardson had released).

Even this fairly lengthy explanation of Gell’s ideas doesn’t fully do them justice, but it does serve to show the power and potential of his theory to help us understand artworks and what they can do in the world. The index-artist-prototype-recipient nexus applies not just to representational art, but to patterns and abstract images, which captivate our attention in different ways. Warren Boutcher has applied it to literary texts. At a time when we are all marvelling at “AI Art” drawn from a vast dataset of other artists’ indices according to instructions written by users and code written by programmers, Gell potentially offers a fresh way to think about artificial intelligence, accountability, art, and agency.

But our concern is with what Gell can teach us about the business of strategy, and specifically strategy which is informed by scenario planning.

Gell and scenarios

Scenarios are created and received aesthetically, and they are intended to have an impact on the world, as they shape strategic decisions. Ramírez and Wilkinson emphasise that “strategic situations are always socially constructed … threats and opportunities are talked into existence”. Trudi Lang has explored the extent to which scenarios are social processes with the capacity to build social capital; the effect of scenario planning on relations between participants may be one of the most valuable outcomes of this kind of work.

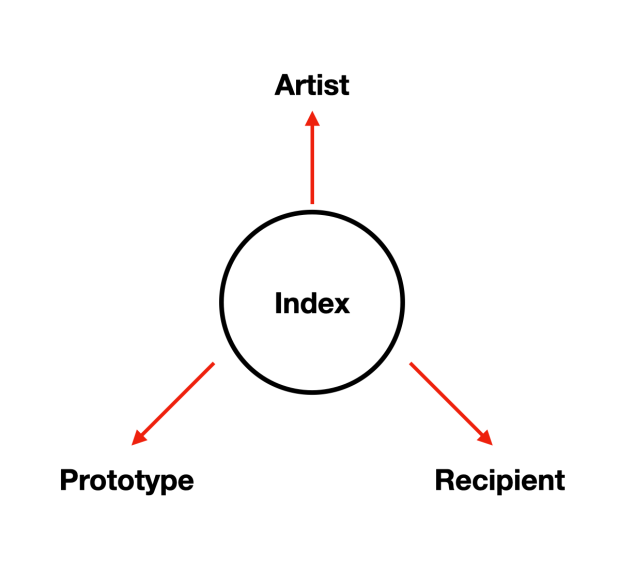

Seen through Gell’s lens, the output of a scenarios process is an index: a document or artefact which captures a conversation about the future context for a strategic issue.

The facilitator is the artist, to the extent that they compile and write up the conversation for wider consumption, making creative and editorial choices. The conversation itself is the prototype, for which the document is meant to stand. Scenario users, including people who were not part of the conversation, are the recipients, on whom the conversation – now decanted into the “vessel” of the scenario index – is meant to have an effect.

The scenario index can take many forms: not just written documents but videos, skits and theatrical performances, immersive experiences, video or board games, and graphic presentations.

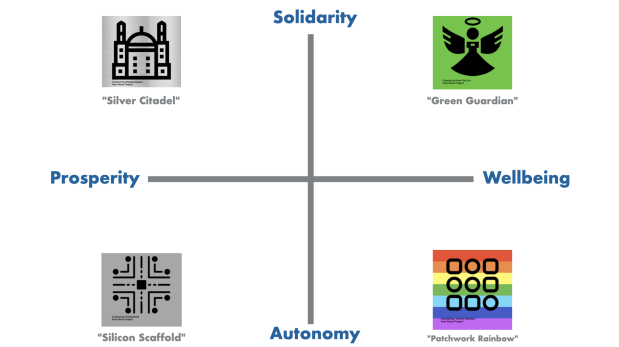

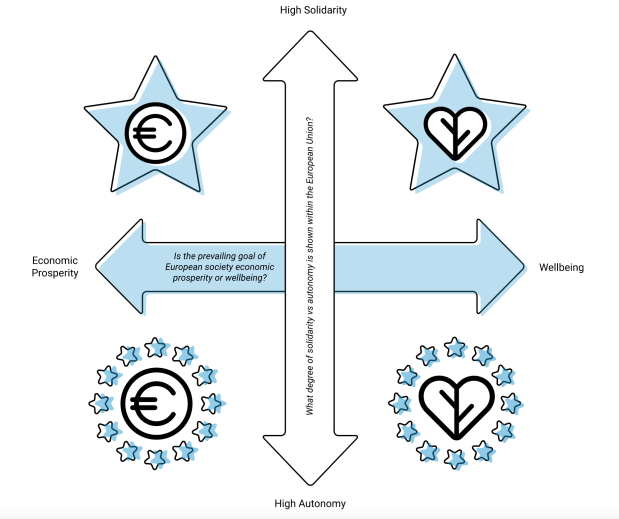

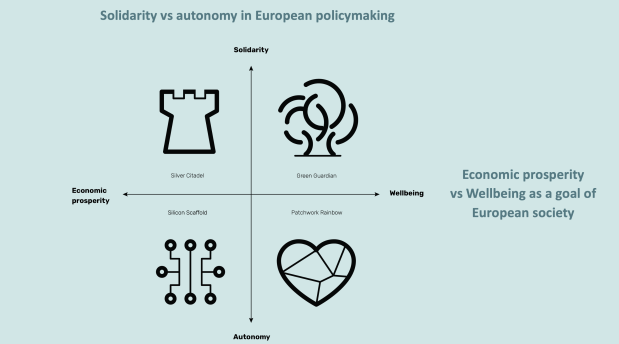

For example, the scenario images from the IMAJINE project, created by Monika Flakowska, represent each future for Europe in 2048 through a depiction of European geography, given a particularly evocative tone and colour, and accompanied by a distinctive icon. These indices, accompanied by the scenario titles, give a first sense of what each scenario might entail – how it might make the recipient feel.

They arose from an iterative process between Flakowska (the artist), the IMAJINE team who commissioned the graphics (the recipients), and the prototype of the scenario material which Flakowska sought to represent. And that prototype itself was an index in the sense that it was a working draft document of earlier conversations, captured and transferred into written prose.

Gell’s approach is useful in letting us explore the ways in which aesthetic objects can be successfully crafted and shared to transform the strategic conversation and the ways in which actors are framing an issue.

This might be to unlearn as well as learn, to trouble received understandings as much as transmit new ones. For George Burt and Anup Karath Nair, scenario planning is a process “by which individuals and organisations acknowledge and release prior learning (including assumptions and mental frameworks) in order to accommodate new information and behaviours.”

In an interview I conducted in 2020, Betty Sue Flowers adds that once prior assumptions have been “unfurrowed” by a scenario, and thinking has been freed from the old rut, new seeds of thought can be planted. She also emphasises that scenarios are produced collectively. This presents particular challenges in their construction: “Writing poetry, you’re by yourself, but when you’re producing scenarios … you’re really herding cats, and often working with a lot of people who are smart and have strong opinions.”

Flowers continues:

When you’re writing a story with a lot of people in a scenario workshop, you listen in a slightly different way to the other participants. I’m listening for the story that wants to emerge. […] I’m trying to sense the stories that are emerging from people talking about various bits and pieces of the world, of the future that might come to be.

In these situations, is there a story somewhere “out there” which the collective are reaching for, and you can see it by virtue of where you’re training your gaze while they’re busy talking – or are you yourself creating the story by how you selectively piece together the mosaic of their individual contributions?

Every observer disturbs the system, especially one who is trying to find images that will hold things together in one piece. I’m mangling it, but I try to hear what is emerging from what they are actually saying. That’s where the fun is for me, because it’s not my story, not something that I thought up but something I hear and then retell.

It resembles an ancient form, oral storytelling. You listen to people, hear the story and tell it your way, and then someone else, hearing you, will retell it again their way. It’s more word-of-mouth; I really think of scenarios, initially at least, as stories that are told by and to groups. They’re not primarily intended to be read. They are more like folk forms than literary forms.

The nature of scenarios as a collective enterprise means that the facilitator must work in the service of the overall project, knowing when to intercede and when to step back. Perhaps the artform it’s most akin to is movie-making; like Ramírez and Wilkinson, authors of the Oxford Scenario Planning Approach, I’m fond of the cinematic metaphor for scenarios, which goes all the way back to Leo Rosten coining the term for use at the RAND Institute.

Movie-making is similar to scenario planning in that it involves wrangling a great number of participants in pursuit of creating an aesthetic experience which will have an impact on an intended audience.

A panel discussion at Lincoln Center commemorating the 20th anniversary of Steven Soderbergh’s The Limey offers useful examples. As the panel participants explain, the 1999 thriller was initially written and edited in a conventional order, only for it to become evident in post-production that a more challenging non-linear edit would produce a more provocative movie.

The elements that had been shot according to the original plan had to be juxtaposed in fresh, sometimes counterintuitive ways to turn a so-so movie into something that was stranger, more compelling, and would prove still worthy of commemoration two decades later.

Even during production, it was necessary to shape the interventions of the cast and crew in order to achieve a vision which was true to the prototype – the story which was seeking to be told through the collective endeavour. As Soderbergh puts it:

Everybody’s making their own movie. You realise at a certain point that … you have a certain movie in your head and it is not the movie [other cast and crew members] have in their head, and you’ve got to figure out how to reconcile these things.

Lesley Ann Warren, one of the movie’s cast, gives the example of a farewell scene in which she felt that her character would be very emotional. Prior to shooting, she was preparing herself to express the distress that she thought her character would display. Director Soderbergh kept coming over and interrupting her process by telling a long-winded, mediocre joke. When it came time to shoot, she had been unable to work herself into the emotional state she had been aiming for. In the panel at Lincoln Center, she explained:

When it was over, I said to [Soderbergh], “What was going on? What were you doing?”

And [Soderbergh] said, “I knew that if I let you start crying, you’d never stop.”

And that wasn’t right for the character, as [Soderbergh] saw it…Each actor and character comes with their own take on what’s going on, and it is up to – one hopes – a brilliant director to see the entire picture, and utilise what the actor can bring.

And what of the “finished” scenarios product, the index itself?

It is a way to provoke further strategic conversation, in much the same way as an artwork only fully comes alive when it finds a recipient. As Ramírez and Wilkinson write, drawing on Carlos Fuentes: “[N]ever again should we have only one voice or reading. Imagination is real and its languages multiple.”

The scenario index is similar to the malanggan carvings of Papua New Guinea’s New Ireland, one of Gell’s examples.

These carvings temporarily store memories for particular recipients during a ceremony, and are disposable once those memories have been processed. As Boucher explains:

When an inhabitant of northern New Ireland dies, indexes of their agency still abound everywhere (i.e. their gardens and plantations, wealth and houses, wives and husbands), but they are not concentrated anywhere in particular. So all the dispersed ‘social effectiveness’ of the decease is collected into a single memorial carving of an ancestral figure […] A whole political economy works by means of these carvings.

The image of the deceased becomes a “distributed object”, “sharing its actual efficacy as though it were a limb.” The malanggan contains all the social effectiveness of the deceased, which can then be parcelled out and redeployed among attendees at the ceremony, so that the agency of the deceased is, in Gell’s words, “perpetuated and reproduced”.

As the malanggan serves as the vessel for the agency of the deceased, a scenario set serves as the vessel for the strategic conversation which was conducted by participants during the scenario planning process. Their insights, perspectives, and contributions to a set of imagined futures intended to challenge current assumptions and expectations about what is unfolding are decanted into the “index” of the scenario set and can then be redeployed in new strategic conversations with new recipients in new settings.

It is not always easy to identify directly how a scenario planning process has informed decisions being taken by a community or organisation, but thinking of scenarios in this way helps us to understand how the collated insights of a future-oriented strategic discussion can be passed onwards and “leave their fingerprints” on decisions of consequence.

Normann and Gell’s Nexus

Oxford-style scenarios share with Gell’s theory of art and agency a deep concern with context.

In Ramírez and Wilkinson’s approach, scenarios are constructed from the interplay of factors in the contextual environment which are perceived to lie beyond a scenario user’s direct control. As those uncertainties play out in plausible futures, they redraw the transactional environment of actors and dynamics which the scenario user perceives that they can influence directly. In this way, scenarios become a question of “the context of the context”; not so much a “futures methodology” as a way of attending to the causal textures and perceived uncertainties of the here-and-now.

Gell, interested in the social efficacy of art, is equally concerned with context and the limits of agency, including when it is decanted into an index.

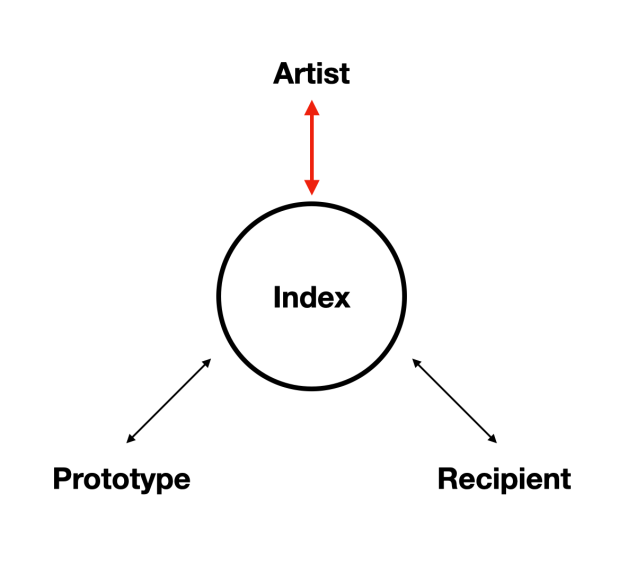

For Gell, the index exists in the overlap between the artist’s sphere of influence and the recipient’s sphere of receptiveness. Together, the “agency” of the artist and the “patiency” of the recipient co-create the social efficacy of an artwork.

This leads us to a deeper resonance with the work of Richard Normann. One of Normann’s abiding interests was the design of systems through which value can be co-created, initially described as “value constellations” by Normann and Ramírez, and later taken up by Ramírez and Ulf Mannervik with their notion of “value-creating systems“.

Value-creating systems, in place of value-chains, focus on how different actors come together to co-create value, in much the same way that artists, recipients, and prototypes all contribute to the value of Gell’s index.

Strategy which takes such an approach can seek to build new collaborative arrangements which generate new value and can even expand Ramirez and Wilkinson’s transactional environment, so that factors which previously seemed to be beyond our direct control now come within our perceived sphere of influence as we build new partnerships and relations.

Such systems are orchestrated by the so-called “configuring offering”, a move which invites other actors into a new alignment. An example is the VISA or Mastercard payment cards which serve to enrol retailers, consumers, and banks into a single system which reduces contextual uncertainty and increases value for each participant.

In a video presentation on his reading of Gell’s work, Boutcher says that “We need new ways of talking about the contexts of objects…Context in Gell’s universe is something very specific; it’s the way in which a particular artefact is described by participants in a culture as indexing agency relations at that time.”

VISA cards or Mastercards can be understood as indices on Gell’s model, as well as configuring offerings in a value-creating system. Furthermore, strategic artefacts or indices, including scenarios, can serve to change perceptions and re-write relations, allowing actors to enrol in new systems of co-creation of value.

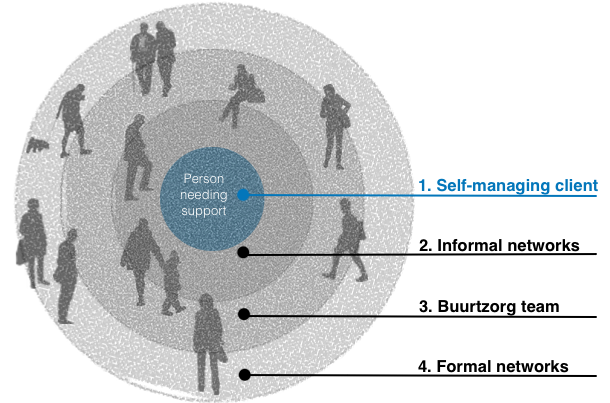

The vision of resilient, collaborative, networked strategy which emerges from the work of Normann, his collaborators, and successors, is built on the idea of orchestrating systems of value co-creation between actors. It can be linked to Gell’s recognition of the power of art to cause such orchestration. This might include the art of political speech and sloganeering, but also elegant organisational design such as the Buurtzorg model of self-managing teams leading client-centred community care.

It also includes the power of creative acts to move and inspire a movement – from the iconography of Joan of Arc to AJ Cronin’s book The Citadel, a novel that captured and helped channel the public mood in postwar Britain which led to the formation of the National Health Service. These indices, in different ways, have helped a wide range of actors to find common cause and co-create value within different contexts.

The enduring art of strategic conversation

In Geoff Dyer’s book The Last Days of Roger Federer, he talks about the enduring power of Bob Dylan’s songs across a lifetime of listening. “It’s not that his music never ages; it keeps step with our own ageing in a way that Freddie Mercury or even Joe Strummer never do,” Dyer writes. “This is not because they died young; it’s because we’ve grown old and out of the music they made.”

With Strummer and Mercury, Dyer says, despite the sincere appreciation he has for their songs and the good experiences he had listening to them in the past, “There’s nothing left to hear”. But, he goes on,

I’ll be listening to Dylan, to new and old versions of songs I’ve been listening to for more than forty years, with undiminished wonder, til the end of my days, hopefully after Dylan himself is no longer around, when the incredible fact that he exists, that we could probably go to see him play somewhere tonight, no longer holds true.

Something similar is true of the work of Normann and Gell, preserved as they are in the indices of books like Art and Agency or Reframing Business, like the social power of the deceased which resides and endures in the malanggan carving.

Gell gives us a way to understand how scenarios are made, communicated, and affect the world. Art and Agency helps us to understand what is going on when we observe, participate in, or make use of scenarios – and to more thoughtfully design scenario processes and products, thinking in terms of prototypes, artists, and recipients mediated via the scenario’s “index”.

Scenarios are the art of strategic conversation, as Kees van der Heijden reminds us, after all — and conversations can endure. The nature of the index means that it can go on, and go beyond the living moment of a discussion: whether that is a strategic insight travelling far and wide beyond the immediacy of a scenarios workshop, or a work of art, or still-vital scholarship, which is passed on to us down the generations.

One thought on “Scenarios: Their Ends, Art, and Agency”